When autocomplete results are available use up and down arrows to review and enter to select.

Central bankers are considering two CBDC approaches: wholesale and retail. Each form comes with a different infrastructure with different implications for financial institutions.

A wholesale CBDC is a digital currency designed for use by financial institutions to enable the payment and settlement of transactions between banks.

In a developed economy with an efficient real-time gross settlement system like Fedwire, a wholesale CBDC would not be a vast improvement to the current domestic market infrastructure in place.

However, in cross-border transactions that involve several intermediaries, a high level of complexity, and significant cost today, a wholesale CBDC could simplify and create efficiencies in the process.

Conversely, a retail CBDC is accessible to the public for use by individuals and businesses.

The global COVID-19 pandemic highlighted friction in the U.S. payments system as people used less cash, and the government sought to deliver stimulus funds with speed and scale. A retail CBDC could open new policy options, such as direct transfers into CBDC digital wallets when dispensing disaster relief or stimulus efforts while carrying out fiscal and monetary policy.

A common misconception is that central banks create most of the money in circulation. In practice, most of the funds held and used by people in the U.S. today are not physical “public money” issued by the Federal Reserve, but digital “private money” created by commercial banks.

Central banks are more cautious with retail CBDC because they would be entering unchartered territory, mainly digital money to the public that until now has been reserved for commercial banks.

One of the risks with a retail digitalized instrument issued by the central bank is bank disintermediation.

There could be a significant drain on retail deposits if people substitute retail CBDC for commercial bank deposits, thereby affecting commercial banks' funding. This could have a significant economic impact if critical bank activities like consumer lending and small business financing are curtailed.

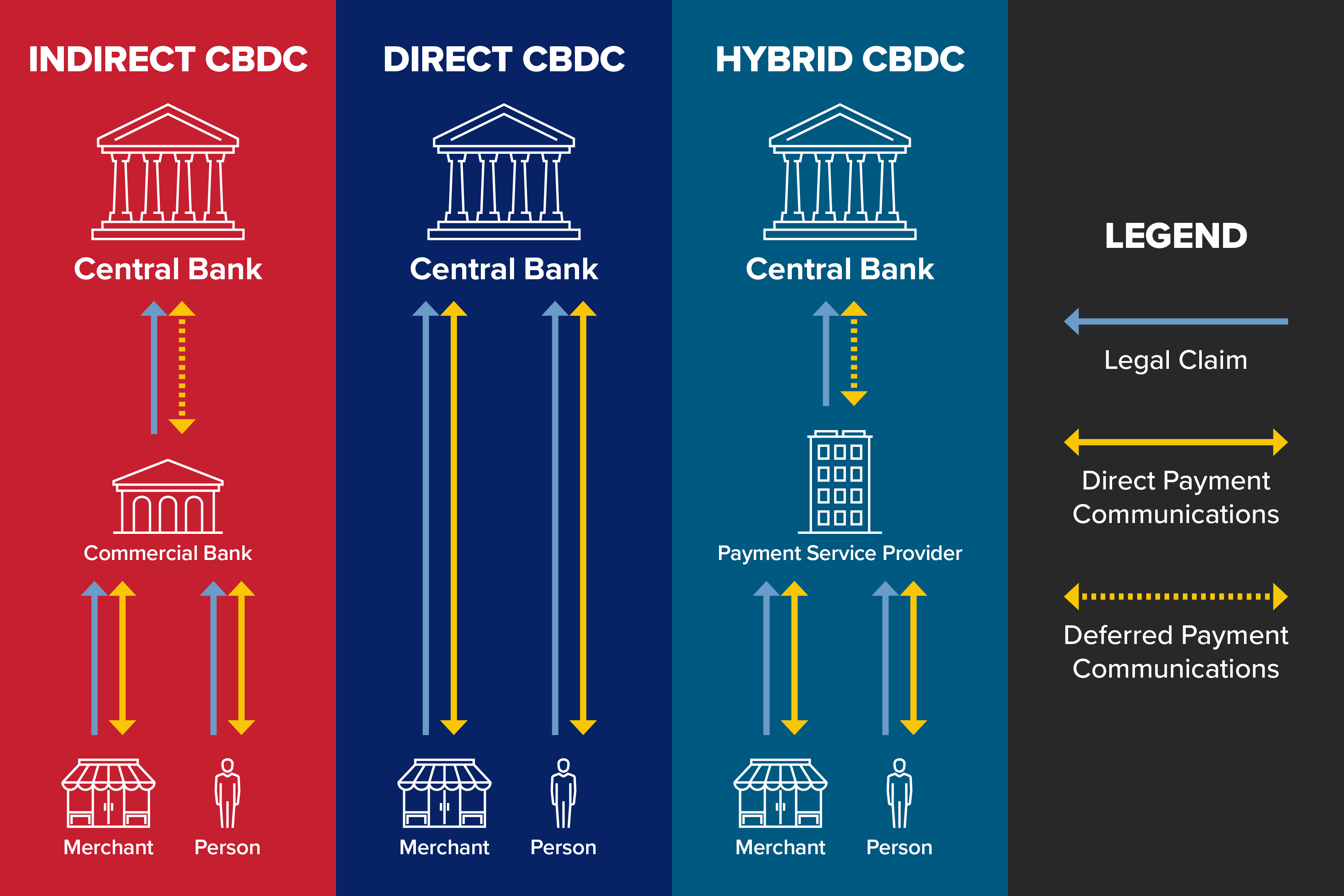

A key consideration of a retail CBDC is how the digital asset will be structured. Three types of business models being explored around the globe are: 1) Direct Model, 2) Indirect Model, and 3) Hybrid Model.

A direct CBDC makes it possible for everyone, from community banks to informal gig workers, to deposit their money directly with the central bank. It would be like having a central bank “checking account” for essential payment services: receiving, holding, spending, and transferring money.

The direct model raises critical concerns. In times of crisis, people could move their money from banks to the central bank, creating bank runs that would exacerbate a troubled economy.

Even in normal times, if a significant number of bank deposits shifted to the central bank, banks could lose an inexpensive source of funding and might be challenged to meet demand for credit, potentially impacting bank viability and hampering economic growth.

A direct model also would disrupt the existing two-tiered banking system and create problems that outweigh potential efficiency gains. Distributing digital currency directly to citizens would require the Federal Reserve to establish a financial services infrastructure that would transfer massive technological and operational risk from the private commercial banking sector to the central bank.

The Federal Reserve would be required to assume a range of responsibilities, such as clearing, onboarding, know your customer (KYC) monitoring, transaction verification, ongoing due diligence, and dispute resolution.

To avoid displacing financial institutions, central bankers have generally been exploring models of indirect CBDC or two-tiered infrastructure.

In this scenario, the Federal Reserve would issue a CBDC to regulated and supervised financial institutions, which would then distribute the CBDC to the public through electronic wallets. This model would preserve the valuable role of community banks.

Even so, with the Indirect Model, there are concerns about the potential migration of bank balances to the central bank. Some experts are contemplating features to make national digital currencies less attractive to hoarding.

One proposal would enable CBDCs only for payments. Another would establish a lower interest rate, a negative interest rate, or even a tiering of interest rates by volume of the retail CBDC. An alternative solution would limit the amount of CBDC a person can hold to address the leakage of bank funding.

Still, the overall risks and impacts of this CBDC model remain unclear and ICBA is monitoring closely on behalf of the community banking industry.

The hybrid distribution infrastructure blends the indirect and direct approaches. Also known as the synthetic model, both banks and licensed private entities would be authorized to issue “digital dollars” fully backed by central bank reserves.

Consider PayPal or a similar fintech performing this function. Consumers would have little or no recourse to recover their funds if an entity that is not FDIC-insured were to fail.

Allowing intermediary organizations lacking the enhanced consumer protection and regulations of supervised financial institutions to offer retail banking products could create more complexity in operational structures and heighten risks, including increased cybersecurity threats.

Although there is a lack of clarity today about how the Federal Reserve will structure the digital dollar, the ultimate model will undoubtedly have wide-reaching effects for community banks and the U.S. payments system.

In the next blog post, we will dive deeper into other design considerations for the future of money.

Nasreen Quibria is ICBA vice president of emerging payments and technology policy.