When autocomplete results are available use up and down arrows to review and enter to select.

By Noah Yosif

The coronavirus pandemic has exacted an immense toll on families, employees, and their communities nationwide in just nine short months since it was first discovered as a novel strain of pneumonia.

The coronavirus pandemic has exacted an immense toll on families, employees, and their communities nationwide in just nine short months since it was first discovered as a novel strain of pneumonia.

While policymakers continue debating new approaches to mitigate its ongoing impact, one issue has attracted newfound scrutiny as the pandemic’s economic consequences unfold: How will these financial pressures affect the U.S. housing market?

This is an issue all too familiar to community banks. Only a decade earlier, they grappled with similar questions amid the fallout from the global recession emanating from the housing market.

Unfortunately, any comparison between the economic calamities of today and 10 years prior risks an apples-to-oranges fallacy. The Great Recession of 2008 was the result of market-specific stressors—predatory credit products, maturity mismatches, and regulatory negligence—while the ongoing coronavirus recession has nonmarket origins as a virus curbing consumer and business activity.

The Great Recession of 2008 also caused sector-specific unemployment that affected certain professions more than others, while the ongoing slowdown in economic activity caused by the coronavirus recession has triggered broad increases in unemployment affecting every sector of the economy.

Finally, financial institutions were hard hit during the Great Recession of 2008 via their heightened exposure to the housing market. Today, given the non-economic origins of the ongoing coronavirus recession, banks – and more specifically, community banks - are well-positioned to be a leader in the eventual recovery.

Examining the present crisis from this perspective will yield a better understanding of the challenges and opportunities facing community banks in the current housing market. With these fundamentals in mind, we will explore three important questions:

In lieu of federal unemployment benefits in conjunction with a long-term evictions moratorium approved by Congress, housing advocates have raised concerns of an impending eviction crisis that leaves many renters, as well as some homeowners, vulnerable to housing insecurity due to their inability to make monthly payments. Such a phenomenon would have severe repercussions for the banking industry, which currently sports a $5.1 trillion residential and mixed-use real estate portfolio.

Community banks hold $2.4 trillion in outstanding residential and mixed-use real estate loans, accounting for 48 percent of real estate loans made by the banking industry and 22 percent of all such loans made by banks and other financial institutions.

By contrast, community banks hold just $220 billion in multifamily loans, which carry the highest risk of default in an eviction crisis scenario, amounting to just 10 percent of their total real estate portfolio and 23 percent of the total multifamily loan market.

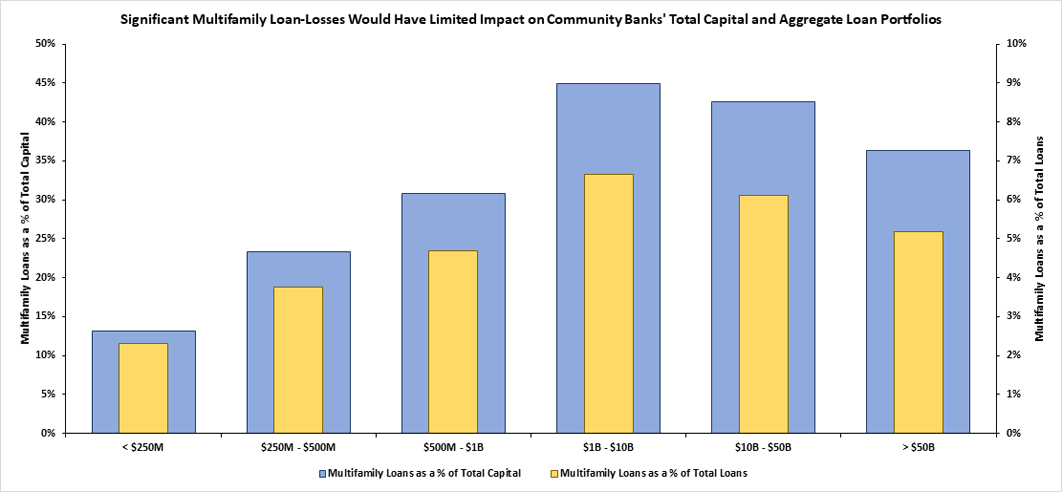

Community banks’ smaller multifamily portfolios also offer significant insulation to their total capital in the event of an eviction crisis. Figure 1 compares the percentage of multifamily loans held by community banks as a share of their total capital, the sum of their tier-1 and tier-2 capital, and their aggregate loan portfolios.

Multifamily loans at community banks under $1 billion account for 13 percent to 31 percent of their total capital, while larger community banks are at a slightly higher risk, with multifamily loans lowering excess capital levels to between 7 and 16 percent above the requirements for a “well-capitalized” designation.

Therefore, if 25 percent of their multifamily loans went into default—an extreme and unlikely scenario—community banks would still preserve 80 percent of their capital after accounting for these loan losses. Of 5,079 community banks, 69 institutions had a significant concentration of multifamily assets equating to 25 percent or more of their aggregate loan portfolios.

Figure 1: Share of Multifamily Loans by Bank Asset Size (source: FDIC)

If the United States averts an eviction crisis, unemployment due to sustained lockdowns and social-distancing measures could still create significant headwind for the housing market, as increased numbers of unemployed individuals are unable to pay their rent or mortgages without financial assistance.

As the coronavirus recession continues to exacerbate outstanding socioeconomic inequalities in the United States, certain industries have been acutely affected by the disease and its related containment efforts, which has produced uneven economic consequences at a local level, often depending on the occupational composition of a community.

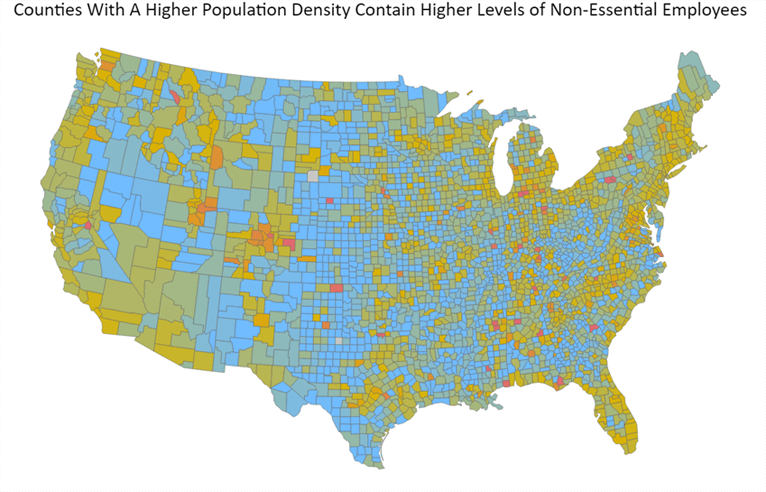

In Figure 2, we identify communities at a higher risk for unemployment leading to vulnerabilities in housing security given the prevalence of nonessential workers in industries such as restaurants, travel-related services, and recreational facilities. Counties in blue have a lower concentration of non-essential workers, while counties in yellow and red have a higher share of non-essential workers.

Figure 2: Prevalence of Non-Essential Employees by County Excluding Alaska & Hawaii (source: Census Bureau)

These workers and their establishments are often concentrated in densely populated areas, placing urban localities and states with higher population densities at an elevated risk for widespread unemployment, as sluggish economic activity forces more furloughs and layoffs that depress income and increase housing insecurity. But how do these dynamics affect community banks and their real estate portfolios?

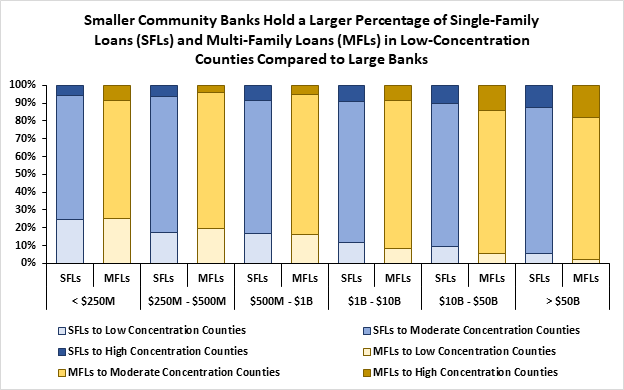

Figure 3 examines the percentage of single-family loans (SFLs) and multifamily loans (MFLs) originated by community banks in counties with varying concentrations of nonessential workers. While nonessential workers are not necessarily indicative of higher unemployment, they are at an elevated risk of unemployment as a consequence of protracted economic inactivity. The percentage of their portfolios comprised of loans in low-concentration counties is three times as high for the smallest banks compared to larger banks.

Figure 3: Distribution of Real Estate Loans by Bank Asset Size (source: HMDA)

The coronavirus pandemic and recession continue to impress long-term changes to the U.S. housing market, from disrupted homebuilder supply lines to stagnating buyer demand. These effects will vary in severity and duration, as local markets are forced to cope with adjusting their operations in accordance with public health guidance, in addition to any consequent growth or depression in economic activity.

However, there are two demand-side trends likely to affect the U.S. housing market at large stemming from the changing nature of work: an increased demand for broadband and a renewed interest in suburban and rural properties.

A growth in remote work policies has generated increased attention to a lack of digital hotspots in communities across the country and demand for greater access to high-speed broadband. This demand will drive home sales in communities with greater broadband capabilities as well as the construction of smart homes with technological features that supplement remote-work needs.

Much of this demand will emanate from rural and suburban areas, which have become increasingly attractive to buyers seeking to distance themselves from high-density metropolitan areas, due to an increased risk of exposure to the coronavirus and their high cost of living.

With more companies offering extended, if not permanent, remote-work policies, we can expect to see an increase in suburban and rural housing construction as well as a general rise in existing home prices as these markets become more competitive.

According to statistics from Zillow, the average volume of home sales increased by 1 percent in urban counties compared to 3 percent within suburban and rural counties between February and July 2020. These newfound demand dynamics present major opportunities for community banks.

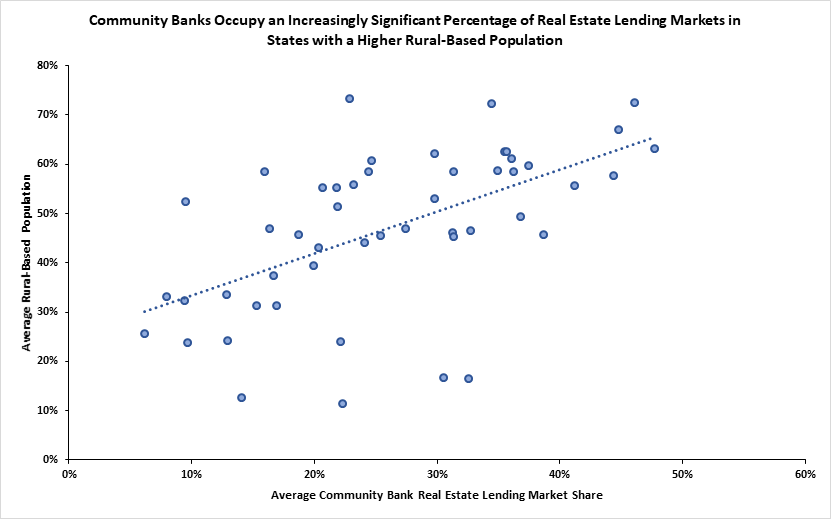

As per Figure 4, community banks occupy a significant percentage of the real estate lending market in suburban and rural areas, which would enable them to expand their portfolios through attracting new business.

Figure 4: Relationship between Community Banks’ Real Estate Market Share and Rural-Based Population per State (HMDA)

In conclusion, there are not many certitudes concerning the eventual trajectory of the U.S. housing market. Yet in a year replete with political, economic, and social transformation due to the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, there are not many certitudes at all.

What we do know is the data today offers a strong case for cautious optimism among community bankers and their real estate portfolios. In an event of widespread evictions, which remains unlikely, community banks are well-capitalized to weather significant losses. Meanwhile, their risk is geographically dispersed to cope with long-term repercussions from this recession, including unemployment and depressed economic activity.

Most importantly, burgeoning trends in demand indicate increased interest in the suburban and rural localities that community banks know best, offering new opportunities for business just outside their doorstep. These are some of many budding trends which indicate community banks are poised to thrive tomorrow as they do today, within a brave new housing market.

Noah Yosif is ICBA assistant vice president of economic policy and research.